Spanking

Background

Physical punishment (or corporal punishment) is commonly defined as “any punishment in which physical force cause[s] some degree of pain or discomfort, however light” (Sege et al., 2018).

Spanking is a type of physical punishment commonly defined as “physically noninjurious, intended to modify behavior, and administered with an open hand to extremities or buttocks” (Bauman & Friedman, 1998).

Recent estimates of spanking in the United States vary widely with common ranges of 35% to 80%, but all estimates have shown recent decreases (Finkelhor et al., 2019; Mehus & Patrick, 2021; Ryan et al., 2016; Gershoff et al., 2018).

There is a spectrum of views on spanking and discipline more broadly, and these steelmen are just a starting point. One common alternative to physical discipline (i.e. authoritative parenting) includes timeouts and privilege removal (e.g. behavioral parent training) but other approaches disagree with all forms of discipline (e.g. exclusively positive parenting). In addition, there is a question of whether such views apply universally or depend on context.

Steelman: Mild spanking may reduce inappropriate behavior as well or better than other methods, eliminating physical punishment may have unintended negative consequences, and the burden of proof is on those proposing to change a widespread practice without superior evidence over conditional spanking

- In four randomized clinical studies, mild spanking showed reduced defiance in clinically oppositional 2- to 6-year-olds during timeouts compared to children deciding their release or parents holding children (Bean & Roberts, 1981; Day & Roberts, 1983; Roberts, 1988; Roberts & Powers, 1990).

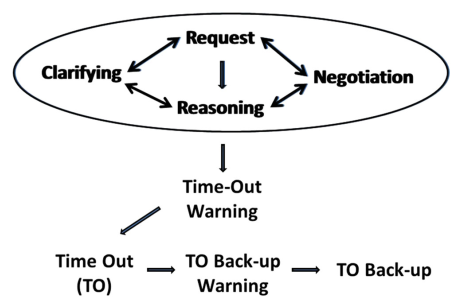

- A meta-analysis of mostly prospective longitudinal studies by Larzelere & Kuhn (2005) suggests a limited type of spanking called conditional or backup spanking (noninjurious and only after failed reasoning or timeouts) may reduce defiance and anti-social behavior in 2- to 6-year-olds compared to all but three other disciplinary methods which showed similar outcomes (Larzelere & Kuhn, 2005; Larzelere & Kuhn, 2005b; Larzelere & Fuller, 2019).

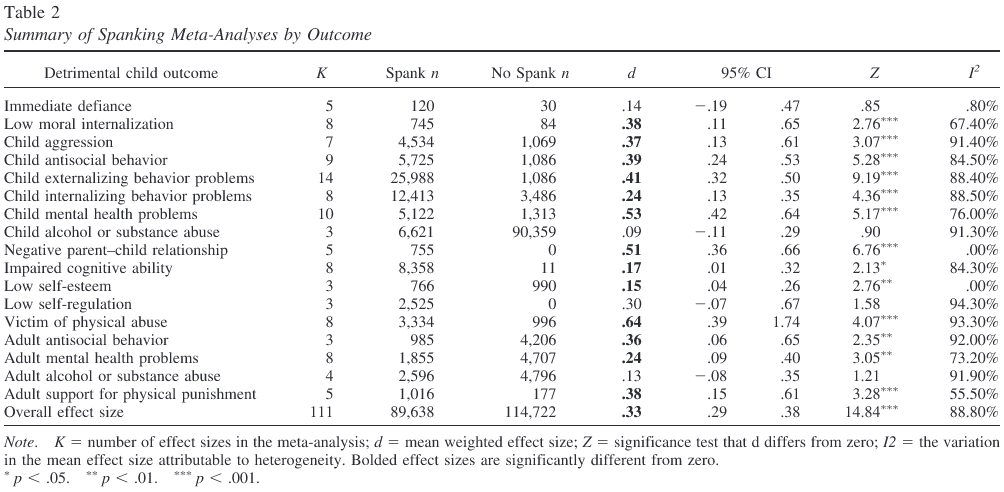

- The claimed negative effects of customary spanking in commonly cited meta-studies (Gershoff & Grogan-Kaylor, 2016; Gershoff, 2002; Heilmann et al., 2021) may be due to residual confounding (Ferguson, 2013; Larzelere et al., 2018b; Larzelere et al., 2004; Larzelere et al., 2010; Larzelere, 2008), methodological bias (Larzelere et al., 2018c), longitudinal study bias (Larzelere et al., 2018d), selection bias (Larzelere & Cox, 2013), imprecise survey results (Larzelere et al., 2018), and/or inadequate statistical controls (Larzelere et al., 2022). Analyses using similar approaches found results potentially as harmful as spanking for corrective actions of parents and professionals such as helping with homework and psychotherapy, which suggests that longitudinal analyses may be biased against corrective actions through statistical biases such as Lord’s paradox and invalid ANCOVA assumptions (Lin & Larzelere, 2020).

- Sweden banned spanking in 1979 and there is some evidence this was correlated with subsequent significant increases in alleged criminal assaults against and by minors from 1981 to 2010, including physical child abuse, criminal assaults by minors against minors, and rapes of children under the age of 15 (Larzelere et al., 2013; Larzelere & Johnson, 1999; Larzelere, 2004; Larzelere, 2008).

- Spanking is overused (Bauman & Friedman, 1998b; Larzelere et al., 2019) but physical punishment is opposed without sufficient evidence of an effective alternative and with the potential for unintended consequences as possibly seen in Sweden (Larzelere et al., 2019; Larzelere et al., 2013; Larzelere et al., 2018e), loss of potential benefits (Baumrind, 1973; Baumrind, 1996), or reduced thriving (Larzelere & Raumrind, 2010).

- Given that spanking has been used in most previous generations, we don’t know the impact of eliminating such disciplines, and Sweden suggests potential problems with such an approach, then the burden of proof is on those proposing to overturn such a widespread practice, and alternative methods should be evaluated relative to conditional spanking.

Response: Non-physical punishment alternatives also perform well, there are potential negative long-term consequences to physical punishment, the Swedish data and hypothesized unintended consequences are tentative and disputed, and the burden of proof is on those proposing physical punishment

- The cited randomized clinical studies did not test non-disciplinary alternatives (during the timeouts or instead of them), and found similar results for a non-physical punishment of barrier enforcement instead of spanking (Day & Roberts, 1983; Roberts, 1988; Roberts & Powers, 1990).

- The cited meta-analysis in Larzelere & Kuhn (2005) only evaluated disciplinary methods, and two non-physical methods showed similar positive impacts (Larzelere & Kuhn, 2005c).

- There are correlations between corporal punishment and increased psychopathology and violence (Cohen & Brook, 1987); increased serious felony convictions, traffic violations, violent behavior under influence of alcohol, and aggression to spouses (Lefkowitz et al., 1978); declines in school engagement (Font & Cage, 2018); other potential consequences as an adverse childhood experience (ACE) (Afifi et al., 2017; Bevilacqua et al., 2021); greater neural activation to fearful faces which may be similar to children experiencing more severe violence (Cuartas et al., 2021); and reduced empathy for others, increased aggression, increased risk of physical abuse & injury, increased anti-social behavior, poorer mental health, increased anxiety, increased depression, increased alcohol and drug use, poorer relationships with parents including estrangement, increased behavioral problems, less moral internalization, less long-term compliance, and increased likelihood of violence against their own children (Gershoff & Bitensky, 2007; Gershoff & Grogan-Kaylor, 2016; Heilmann et al., 2021; Gershoff & Grogan-Kaylor, 2016b).

- There is debate about the potential negative effects of the Swedish ban on spanking (Holden et al., 2017; Durrant, 1999; Durrant, 2005; Bussmann et al., 2010) and the ban was also correlated with decreases in youth suicides and involvement in theft and drugs (Durrant, 2000).

- Given that non-mild spanking is widely accepted as problematic (Bauman & Friedman, 1998b; Larzelere et al., 2019), that non-physical punishment alternatives generally perform well (Gershoff et al., 2019), that there are correlations with physical punishments and negative long-term consequences, and that the Swedish data and hypothesized unintended consequences are tentative and disputed, then the burden of proof is on those proposing physical punishments.

Meta-comments

-

Bauman & Friedman (1998)

- “Data about corporal punishment are marshaled by two opposing armies of professionals and researchers […] Each can find articles and studies to cite in the service of their arguments. The research results are contradictory, in part because the methods are flawed, in part because conclusions are not always justified by the data, and in part because conclusions of a few studies on unusual samples are generalized inappropriately.”

- “Based on this article, it seems that most studies suffer severe methodological problems. Those that have external validity, that is, with representative samples of children prospectively studied over a long period of time, have generated contradictory results; however, in the authors’ view, the studies by Baumrind and by Cohen and Brook are the most important. Baumrind’s study has a small nonrepresentative sample of middle-class families that were followed intensively over a long period. Her findings show that corporal punishment, when administered in the context of a loving family in an authoritative parenting style, has no long-term negative effects and may actually have benefits; however, Cohen and Brook’s prospective data of a representative sample of children followed over many years show that power-assertive disciplinary techniques, as currently practiced by American parents (including subabusive corporal punishment), is associated with increased rates of psychopathology and violence 8 years later, controlling for several potential confounding factors. The fact that these two studies are contradictory is of great concern.”

- “Another methodological challenge is the validity of self-report data on spanking practices because of the high potential for social desirability bias. Also, many studies interview adults and ask for reports about how they were disciplined as children. Skepticism of such data is warranted due to inaccurate retrospective recall.”

- “One reason for the lack of evidence on spanking is that it is so common. If 90% of parents spank their children, the behavior must be considered normative. Thus, it is likely that people who do not spank are different in many ways from people who do. If the children of this small subgroup have better or worse outcomes than the majority of children who are spanked, how can we possibly attribute it to spanking practices alone? Furthermore, the extent, nature, and intensity of spanking behavior among those who spank is likely to be strongly associated with other behaviors and values, such as religious beliefs, region of the country, how parents themselves were disciplined, type and level of education, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity. All of these factors also affect a child’s risk for violence or psychopathology in adulthood. Finally, spanking as a form of discipline is rarely used in isolation from other aversive disciplinary strategies. Thus, it becomes impossible to disentangle the effects of spanking from other forms of discipline when they so regularly co-occur. The authors identified no studies that successfully studied the effectiveness and consequences of spanking independent of other disciplinary techniques and controlling for covariates.”

- “The inevitable conclusion from a critical, objective review of the scientific research on corporal punishment is that the data are inadequate to permit a conclusion on either its effectiveness or its negative consequences.”

References

53 references

- (Afifi et al., 2017):

Afifi, T. O., Ford, D., Gershoff, E. T., Merrick, M., Grogan-Kaylor, A., Ports, K. A., … & Bennett, R. P. (2017). Spanking and adult mental health impairment: The case for the designation of spanking as an adverse childhood experience. Child Abuse & Neglect, 71, 24-31. DOI: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.01.014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.01.014

- (Bauman & Friedman, 1998):

Bauman, L. J., & Friedman, S. B. (1998). Corporal punishment. Pediatric clinics of North America, 45(2), 403-414. DOI: 10.1016/S0031-3955(05)70015-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-3955(05)70015-8

- (Bauman & Friedman, 1998b):

“Proponents of spanking do acknowledge that certain child-rearing practices are associated with a higher risk for psychopathology in children. Therefore, professionals and researchers who advocate the use of spanking are specific about how and when to use it appropriately: in preschool children aged 2 to 6 years; never in infants or adolescents; with the intention of correction and teaching; not out of anger, frustration, or the desire to hurt; and limited in intensity to one or two strikes by an open hand applied to buttocks or thighs only. It should not be the first and most usual form of discipline. […] By proponents’ own standards, most parents spank their children in ways not advised or recommended. Studies clearly and consistently show that abusive levels of corporal punishment and corporal punishment of children more than 10 years of age are associated with increased psychopathology and increased risk of adult violent and criminal behavior”

Bauman, L. J., & Friedman, S. B. (1998b). Corporal punishment. Pediatric clinics of North America, 45(2), 403-414. DOI: 10.1016/S0031-3955(05)70015-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-3955(05)70015-8

- (Baumrind, 1973):

Baumrind, D. (1973). The Development of Instrumental Competence through Socialization. In A. D. Pick (Ed.), Minnesota Symposia on Child Psychology: Volume 7 (New edition, pp. 3–46). University of Minnesota Press. DOI: 10.5749/j.ctttsmk0.4. https://doi.org/10.5749/j.ctttsmk0.4

- (Baumrind, 1996):

Baumrind, D. (1996). The discipline controversy revisited. Family relations, 405-414. DOI: 10.2307/585170. https://doi.org/10.2307/585170

- (Bean & Roberts, 1981):

Bean, A. W., & Roberts, M. W. (1981). The effect of time-out release contingencies on changes in child noncompliance. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 9(1), 95-105. DOI: 10.1007/BF00917860. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00917860

- (Bevilacqua et al., 2021):

Bevilacqua, L., Kelly, Y., Heilmann, A., Priest, N., & Lacey, R. E. (2021). Adverse childhood experiences and trajectories of internalizing, externalizing, and prosocial behaviors from childhood to adolescence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 112, 104890. DOI: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104890. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104890

- (Bussmann et al., 2010):

Bussmann, K. D., Erthal, C., & Schroth, A. (2010). Effects of banning corporal punishment in Europe: A five-nation comparison. In Global pathways to abolishing physical punishment (pp. 315-338). Routledge. DOI: 10.1007/BF00912184. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00912184

- (Cohen & Brook, 1987):

Cohen, P., & Brook, J. (1987). Family factors related to the persistence of psychopathology in childhood and adolescence. Psychiatry, 50(4), 332-345. DOI: 10.1080/00332747.1987.11024365. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1987.11024365

- (Cuartas et al., 2021):

Cuartas, J., Weissman, D. G., Sheridan, M. A., Lengua, L., & McLaughlin, K. A. (2021). Corporal punishment and elevated neural response to threat in children. Child development, 92(3), 821-832. DOI: 10.1111/cdev.13565. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13565

- (Day & Roberts, 1983):

Day, D. E., & Roberts, M. W. (1983). An analysis of the physical punishment component of a parent training program. Journal of abnormal child psychology, 11(1), 141-152. DOI: 10.1007/BF00912184. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00912184

- (Durrant, 1999):

Durrant, J. E. (1999). Evaluating the success of Sweden’s corporal punishment ban. Child abuse & neglect, 23(5), 435-448. DOI: 10.1016/S0145-2134(99)00021-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(99)00021-6

- (Durrant, 2000):

Durrant, J. E. (2000). Trends in youth crime and well-being since the abolition of corporal punishment in Sweden. Youth & Society, 31(4), 437-455. DOI: 10.1177/0044118X00031004003. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X00031004003

- (Durrant, 2005):

Durrant, J. E. (2005). Law reform and corporal punishment in Sweden: Response to Robert Larzelere, the Christian Institute, and Families First. Winnipeg: Department of Family Social Sciences, University of Manitoba. Retrieved August, 2022 from https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.378.8926

- (Ferguson, 2013):

“If biases and residual confounding can account for the remaining trivial effect sizes, this increases the possibility that a subset of spanking may actually decrease problematic outcomes such as externalizing problems.”

Ferguson, C. J. (2013). Spanking, corporal punishment and negative long-term outcomes: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Clinical psychology review, 33(1), 196-208. DOI: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.11.002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.11.002

- (Finkelhor et al., 2019):

“Fig. 1 Spanked in past year by age of child” (Page 3)

Finkelhor, D., Turner, H., Wormuth, B. K., Vanderminden, J., & Hamby, S. (2019). Corporal punishment: Current rates from a national survey. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(7), 1991-1997. DOI: 10.1007/s10826-019-01426-4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01426-4

- (Font & Cage, 2018):

Font, S. A., & Cage, J. (2018). Dimensions of physical punishment and their associations with children’s cognitive performance and school adjustment. Child abuse & neglect, 75, 29-40. DOI: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.06.008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.06.008

- (Gershoff, 2002):

Gershoff, E. T. (2002). Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: a meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological bulletin, 128(4), 539. DOI: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.4.539. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.128.4.539

- (Gershoff & Bitensky, 2007):

Gershoff, E. T., & Bitensky, S. H. (2007). The case against corporal punishment of children: Converging evidence from social science research and international human rights law and implications for US public policy. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 13(4), 231. DOI: 10.1037/1076-8971.13.4.231. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8971.13.4.231

- (Gershoff & Grogan-Kaylor, 2016):

Gershoff, E. T., & Grogan-Kaylor, A. (2016). Spanking and child outcomes: Old controversies and new meta-analyses. Journal of family psychology, 30(4), 453. DOI: 10.1037/fam0000191. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000191

- (Gershoff & Grogan-Kaylor, 2016b):

“Although the magnitude of the observed associations may be small, when extrapolated to the population in which 80% of children are being spanked, such small effects can translate into large societal impacts.”

Gershoff, E. T., & Grogan-Kaylor, A. (2016b). Spanking and child outcomes: Old controversies and new meta-analyses. Journal of family psychology, 30(4), 453. DOI: 10.1037/fam0000191. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000191

- (Gershoff et al., 2018):

Gershoff, E. T., Goodman, G. S., Miller-Perrin, C. L., Holden, G. W., Jackson, Y., & Kazdin, A. E. (2018). The strength of the causal evidence against physical punishment of children and its implications for parents, psychologists, and policymakers. American Psychologist, 73(5), 626. DOI: 10.1037/amp0000327. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000327

- (Gershoff et al., 2019):

“There is virtually no evidence indicating that physical punishment is beneficial or is a necessary back up when alternatives are ineffective. There is always another way to socialize children that does not involve hitting them. […] There is no body of replicated evidence indicating physical punishment has positive benefits for children. Rather, there are hundreds of studies indicating that physical punishment can be harmful.”

Gershoff, E. T., Goodman, G. S., Miller-Perrin, C., Holden, G. W., Jackson, Y., & Kazdin, A. E. (2019). There is still no evidence that physical punishment is effective or beneficial: Reply to Larzelere, Gunnoe, Ferguson, and Roberts (2019) and Rohner and Melendez-Rhodes (2019). DOI: 10.1037/amp0000474. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000474

- (Heilmann et al., 2021):

Heilmann, A., Mehay, A., Watt, R. G., Kelly, Y., Durrant, J. E., van Turnhout, J., & Gershoff, E. T. (2021). Physical punishment and child outcomes: a narrative review of prospective studies. The Lancet, 398(10297), 355-364. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00582-1. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00582-1

- (Holden et al., 2017):

Holden, G. W., Grogan-Kaylor, A., Durrant, J. E., & Gershoff, E. T. (2017). Researchers deserve a better critique: Response to Larzelere, Gunnoe, Roberts, and Ferguson (2017). Marriage & Family Review, 53(5), 465-490. DOI: 10.1080/01494929.2017.1308899. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2017.1308899

- (Larzelere, 2004):

Larzelere, R. E. (2004). Sweden’s smacking ban: More harm than good. Frinton on Sea, Essex, UK: Families First. Retrieved August, 2022, from https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.491.1313

- (Larzelere, 2008):

Larzelere, R. E. (2008). Disciplinary spanking: The scientific evidence. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 29(4), 334-335. DOI: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181829f30. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181829f30

- (Larzelere & Cox, 2013):

Larzelere, R. E., & Cox Jr, R. B. (2013). Making valid causal inferences about corrective actions by parents from longitudinal data. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 5(4), 282-299. DOI: 10.1111/jftr.12020. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12020

- (Larzelere & Fuller, 2019):

Larzelere, R., & Fuller, J. (2019). Scientific evidence supports customary and backup (conditional) spanking by parents: Update of Larzelere and Baumrind (2010) and Fuller (2009). SSRN. DOI: 10.2139/ssrn.3500544. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3500544

- (Larzelere & Johnson, 1999):

Larzelere, R. E. & Johnson, B. (1999). Evaluation of the effects of Sweden’s spanking ban on physical child abuse rates: A literature review. Psychological Reports, 85, 381-392. DOI: 10.2466/pr0.1999.85.2.381. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1999.85.2.381

- (Larzelere & Kuhn, 2005):

“the effect sizes of conditional spanking compared favorably with alternative tactics for all disruptive behavior problems, including antisocial behavior and defiance. Second, physical punishment competed just as well with alternative tactics for long term outcomes as for short-term outcomes. In fact, the results favored physical punishment over alternatives more for long-term outcomes than for short-term outcomes, but only when the largest retrospective study (Tennant et al., 1975) was included in the analyses. Third, all types of physical punishment were associated with lower rates of antisocial behavior than were alternative disciplinary tactics. […] Fourth, this meta-analysis failed to detect negative side effects unique to physical punishment […] physical punishment fails to teach positive alternative behaviors […] the analyses partially supported the conclusion that nonphysical punishments are just as effective as physical punishment […] The meta-analytic results favored conditional spanking over nonphysical punishments in general for reducing defiance and antisocial behavior. […] Most of the previous evidence against physical punishment does not appear to be unique to physical punishment.”

Larzelere, R. E., & Kuhn, B. R. (2005). Comparing child outcomes of physical punishment and alternative disciplinary tactics: A meta-analysis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 8(1), 1-37. DOI: 10.1007/s10567-005-2340-z. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-005-2340-z

- (Larzelere & Kuhn, 2005b):

“First, physical punishment, like other forms of punishment, does not enhance positive development, but only inhibits inappropriate behavior, such as defiance and antisocial behavior. Second, most types of nonphysical punishment had similar associations with outcomes as did physical punishment, although they had better outcomes only in comparisons with overly severe or predominant physical punishment.”

Larzelere, R. E., & Kuhn, B. R. (2005b). Comparing child outcomes of physical punishment and alternative disciplinary tactics: A meta-analysis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 8(1), 1-37. DOI: 10.1007/s10567-005-2340-z. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-005-2340-z

- (Larzelere & Kuhn, 2005c):

“two forms of nonphysical punishment yielded effect sizes equivalent to conditional spanking. The availability of an equally effective nonphysical punishment has been one rationale for dispensing with physical punishment altogether (Graziano, Hamblen, & Plante, 1996; Straus, 2001). Equivalence of effects makes a poor rationale for a spanking ban for several reasons. Disciplinary tactics with equivalent effectiveness overall may each show superior effectiveness for some children in some situations. Indeed, the barrier method, the most effective disciplinary tactic in this meta-analysis, was ineffective with some children, and a child-determined release from time-out, a relatively ineffective disciplinary tactic, was effective for some clinically oppositional children (Roberts & Powers, 1990). When one disciplinary tactic is not working, parents would benefit from having a range of effective alternatives to turn to, as shown by Roberts and Powers (1990). Moreover, effect equivalence would not be considered sufficient to ban a prescription medication, unless the differences in negative side effects clearly favored other equally effective medications in almost all applications.”

Larzelere, R. E., & Kuhn, B. R. (2005c). Comparing child outcomes of physical punishment and alternative disciplinary tactics: A meta-analysis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 8(1), 1-37. DOI: 10.1007/s10567-005-2340-z. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-005-2340-z

- (Larzelere & Raumrind, 2010):

Larzelere, R. E., & Raumrind, D. (2010). Are spanking injunctions scientifically supported. Law & Contemporary Problems, 73(2), 57–87. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25766387

- (Larzelere et al., 2004):

Larzelere, R. E., Kuhn, B. R., & Johnson, B. (2004). The intervention selection bias: an underrecognized confound in intervention research. Psychological bulletin, 130(2), 289. DOI: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.2.289. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.2.289

- (Larzelere et al., 2010):

Larzelere, R. E., Cox, R. B., & Smith, G. L. (2010). Do nonphysical punishments reduce antisocial behavior more than spanking? A comparison using the strongest previous causal evidence against spanking. BMC Pediatrics, 10(1), 1-17. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2431-10-10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-10-10

- (Larzelere et al., 2013):

“Together, these five trends in Swedish criminal assaults against minors suggest that the way the first spanking ban has been implemented in that country may have increased criminal assaults in that country, in contrast to its intended effect of decreasing violence.”

Larzelere, R. E., Swindle, T., & Johnson, B. R. (2013). Swedish trends in criminal assaults against minors since banning spanking, 1981-2010. International journal of criminology and sociology, 2, 129-137. DOI: 10.6000/1929-4409.2013.02.13. https://doi.org/10.6000/1929-4409.2013.02.13

- (Larzelere et al., 2018):

“Existing meta-analyses […] were limited by the fact that most spanking research is based on parents’ responses to whether or how often they “spank or slap” their child or “use physical punishment,” without excluding spanking with objects of various kinds.”

Larzelere, R. E., Gunnoe, M. L., & Ferguson, C. J. (2018). Improving causal inferences in meta‐analyses of longitudinal studies: Spanking as an illustration. Child Development, 89(6), 2038-2050. DOI: 10.1111/cdev.13097. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13097

- (Larzelere et al., 2018b):

“Our meta-analytic results indicated that the trivial partial effect sizes reported by Ferguson (2013) and replicated herein were more consistent with residual biases than with a true causal effect.”

Larzelere, R. E., Gunnoe, M. L., & Ferguson, C. J. (2018b). Improving causal inferences in meta‐analyses of longitudinal studies: Spanking as an illustration. Child Development, 89(6), 2038-2050. DOI: 10.1111/cdev.13097. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13097

- (Larzelere et al., 2018c):

“In addition, we found that neither the significant “adverse” impact of spanking suggested by the usual β method or the significant “beneficial” impact of spanking suggested by slope predictions was robust enough to overcome the methodological bias of the alternative method. Put another way, it seems likely that the true average causal effect of spanking on externalizing is so close to zero that significant results require residual confounding (in the b method) or regression toward the mean (in slope predictions) in their favor.”

Larzelere, R. E., Gunnoe, M. L., & Ferguson, C. J. (2018c). Improving causal inferences in meta‐analyses of longitudinal studies: Spanking as an illustration. Child Development, 89(6), 2038-2050. DOI: 10.1111/cdev.13097. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13097

- (Larzelere et al., 2018d):

Larzelere, R. E., Lin, H., Payton, M. E., & Washburn, I. J. (2018). Longitudinal biases against corrective actions. Archives of Scientific Psychology, 6(1), 243. DOI: 10.1037/arc0000052. https://doi.org/10.1037/arc0000052

- (Larzelere et al., 2018e):

“Virtually all professionals oppose overly severe physical punishment, a view consistent with these meta-analytic results”

Larzelere, R. E., Gunnoe, M. L., & Ferguson, C. J. (2018c). Improving causal inferences in meta‐analyses of longitudinal studies: Spanking as an illustration. Child Development, 89(6), 2038-2050. DOI: 10.1111/cdev.13097. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13097

- (Larzelere et al., 2019):

“this Comment argues that Gershoff et al. overstated the strength of their causal evidence against spanking. It also expresses concern that researchers are opposing a disciplinary technique without adequate evidence for a more effective alternative. […] Although Gershoff’s et al. (2018) evidence for opposing spanking is insufficient, we recognize that spanking is often overused. […] opposing spanking or alternatives with mostly correlational evidence may hurt families more than it helps them. Clinicians would not eschew a widely used clinical intervention without identifying a more effective alternative. Neither should family psychologists. Causal assertions based primarily on correlational evidence may also undermine the integrity of psychological science.”

Larzelere, R. E., Gunnoe, M. L., Ferguson, C. J., & Roberts, M. W. (2019). The insufficiency of the evidence used to categorically oppose spanking and its implications for families and psychological science: Comment on Gershoff et al.(2018). DOI: 10.1037/amp0000461. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000461

- (Larzelere et al., 2020):

“Figure 1. How authoritative parents combine positive disciplinary responses with enforcement of limits when needed.”

Larzelere, R. E., Gunnoe, M. L., Roberts, M. W., Lin, H., & Ferguson, C. J. (2020). Causal evidence for exclusively positive parenting and for timeout: Rejoinder to Holden, Grogan-Kaylor, Durrant, and Gershoff (2017). Marriage & Family Review, 56(4), 287-319. DOI: 10.1080/01494929.2020.1712304. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2020.1712304

- (Larzelere et al., 2022):

“However, the two previously published meta-analyses of controlled longitudinal studies of spanking do not support spanking bans, due to the trivial size of the average adverse-looking effect of customary spanking in those studies. Moreover, several lines of evidence indicate that this trivial average effect is likely due to inadequate statistical controls rather than an actual adverse causal effect of typical spanking.”

Larzelere, R. E., Gunnoe, M. L., Pritsker, J., Ferguson, C. J., Adkison-Johnson, C., Mandara, J., & Trumbull, D. A. (2022). The Outcomes of Physical Punishment are Typical of All Corrective Actions: A Response to Heilmann et al’s (2021) Narrative Review. DOI: 10.31234/osf.io/5xbnm. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/5xbnm

- (Lefkowitz et al., 1978):

Lefkowitz, M. M., Huesmann, L. R., & Eron, L. D. (1978). Parental punishment: A longitudinal analysis of effects. Archives of General Psychiatry, 35(2), 186-191. DOI: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770260064007. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770260064007

- (Lin & Larzelere, 2020):

“Almost all longitudinal analyses of corrective actions by parents have concluded that they are harmful at worst or ineffective at best, even after controlling for initial differences on the outcome (see Table 1). […] Two such studies concluded that it is counterproductive for parents to help their children with homework. […] Several studies have investigated corrective actions by parents and by professionals with the same types of analyses on the same sample. Those studies found that two corrective actions by professionals, psychotherapy and Ritalin, looked as harmful as spanking when analyzed longitudinally controlling for initial differences on the outcome variable (Larzelere, Cox, et al., 2010; Larzelere, Ferrer, et al., 2010).

We know of no corrective action by parents that has been consistently found to predict beneficial outcomes in the most typical longitudinal analyses. Do parents inadvertently harm their children whenever they try to correct their problems? Or is there something about longitudinal analyses that is biased against corrective actions?

The first step toward solving a problem is recognizing the problem. The replication controversy occurred in psychological science because of failures to replicate, mostly in randomized studies. Corrective actions face a different kind of replication crisis—replicating too often, but for the wrong reasons. Replications will not lead to cumulative progress in psychological science if they are merely replicating systematic biases (Larzelere et al., 2015). If corrective actions are evaluated with unadjusted correlations, we can get very consistent replications (Gershoff & Grogan-Kaylor, 2016). The problem is that unadjusted correlations are biased against all corrective actions, due to the poor prognosis of the problem being corrected (Larzelere & Cox, 2013). Adjusting for preexisting differences in longitudinal studies reduces that bias, but eliminates it only when treatment assignments are completely determined by the covariates. Longitudinal analyses of residualized change scores obtain smaller, but still significant, replicated results against most corrective actions. The problem is that this smaller longitudinal evidence against corrective actions replicates not only for spanking (Ferguson, 2013), but also for all other corrective actions for important problems, whether implemented by parents or professionals, at least to our knowledge.”

Lin, H., & Larzelere, R. E. (2020). Dual-centered ANCOVA: Resolving contradictory results from Lord’s paradox with implications for reducing bias in longitudinal analyses. Journal of Adolescence, 85, 135-147. DOI: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.11.001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.11.001

- (Mehus & Patrick, 2021):

Mehus, C. J., & Patrick, M. E. (2021). Prevalence of spanking in US national samples of 35-year-old parents from 1993 to 2017. JAMA pediatrics, 175(1), 92-93. DOI: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.2197. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.2197

- (Paolucci & Violato, 2004):

Paolucci, E. O., & Violato, C. (2004). A meta-analysis of the published research on the affective, cognitive, and behavioral effects of corporal punishment. The Journal of psychology, 138(3), 197-222. DOI: 10.3200/JRLP.138.3.197-222. https://doi.org/10.3200/JRLP.138.3.197-222

- (Roberts, 1988):

Roberts, M. W. (1988). Enforcing chair timeouts with room timeouts. Behavior Modification, 12(3), 353-370. DOI: 10.1177/01454455880123003. https://doi.org/10.1177/01454455880123003

- (Roberts & Powers, 1990):

Roberts, M. W., & Powers, S. W. (1990). Adjusting chair timeout enforcement procedures for oppositional children. Behavior Therapy, 21(3), 257-271. DOI: 10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80329-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80329-6

- (Ryan et al., 2016):

Ryan, R. M., Kalil, A., Ziol-Guest, K. M., & Padilla, C. (2016). Socioeconomic gaps in parents’ discipline strategies from 1988 to 2011. Pediatrics, 138(6). DOI: 10.1542/peds.2016-0720. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-0720

- (Sege et al., 2018):

Sege, R. D., Siegel, B. S., Flaherty, E. G., Gavril, A. R., Idzerda, S. M., … & Wissow, L. S. (2018). Effective discipline to raise healthy children. Pediatrics, 142(6). DOI: 10.1542/peds.2018-3112. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-3112

Share on

Twitter Facebook LinkedIn

Other topics: